Valuations, the IRS, Probate, and Karma

Joe Meador was a lieutenant with the 87th Armored Field Artillery Battalion. They landed at Normandy on D-Day, fought through France, Belgium, and deep into Germany.

In April 1945 – the waning days of the war – they arrived in the formerly idyllic town of Quedlinburg, home of the Quedlinburg Abbey, built by Otto the Great in 936. The abbey held countless priceless antiquities. All of which the townsfolk had hidden away in a mine shaft to keep them safe.

Not the Monument Men

The men of the 87th were battle-weary, bloodied, and just trying to get to the end of the war unharmed. Then a drunken soldier accidentally stumbled into the mine and the 87th quickly found themselves assigned to protect the treasure trove until the Monument Men arrived. If you’ve read the book or saw the movie you know that the Monument Men were there specifically to take care of exactly this. But they couldn’t be everywhere, so the 87th had sole custody of the treasure for days.

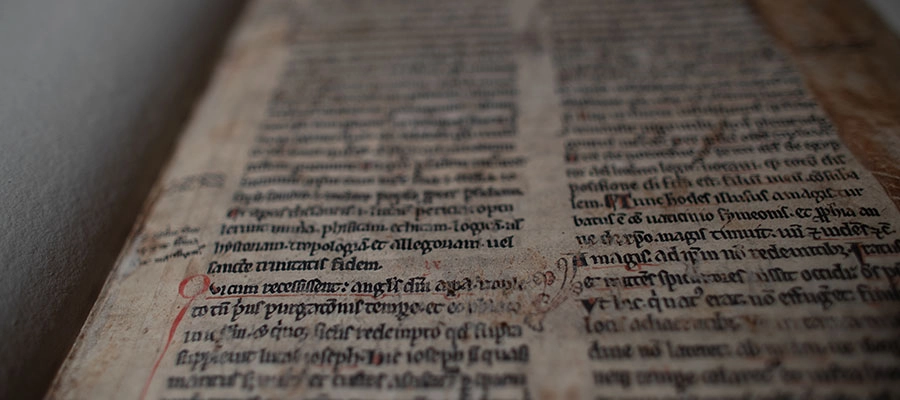

Boring duty for everyone except the tunnels’ new commanding officer, Lt. Meador. He was an art history major from North Texas State with post graduate studies at Biarritz, France. One of his classes was in Illuminated Manuscripts.

It was noticed that he spent a lot of time in the tunnel.

An Epic Art Theft

The Monument Men finally showed up, Joe and his men were relieved, Hitler killed himself, and the war ended.

Several weeks after Germany’s surrender, the Monument Men made a full inventory and found that eight pieces were missing including a medieval illuminated manuscript and the Quedlinburg Gospels. Both books had jewel-encrusted covers.

It was ruled a theft - the largest art theft, in fact, of the 20th Century. The on and off again investigation ended when Quedlinburg became part of East Germany in 1949. It was forgotten by everyone except the residents of Quedlinburg.

Meanwhile, after a short teaching stint, Joe moved back to North Texas and took over his family’s hardware store and became locally renowned for his orchids.

Every once in a while, Joe would gather his employees and show them the ‘marvelous’ books and curios he had inherited from a nebulous relative.

His family, however, knew the truth - Joe had mailed the pieces home from Germany in April 1945 via U.S. Army post.

Sailing Through Probate

Joe died of cancer in 1980, leaving everything to his brother and sister. The total estate was valued at under $125,000; no mention was made of the books or curios during probate, they were wrapped in quilts in a closet.

Somewhere in the mid-80s things began to change. Family members used the books as collateral for a small loan and they were moved to a bank vault for safekeeping. Rumors somehow snuck out of Texas and reached Germany.

In rapid succession, the Soviet Union fell, the Germanys reunited, and a shadowy lawyer started making oblique overtures to art dealers and museums for a ‘once in a lifetime’ acquisition. It took awhile in that pre-internet age but one thread led to another and the Meadors were singled out as the possessors of the missing items.

A Negotiated Sale and the IRS

Finally, around 1991, the German government and representatives from Quedlinburg met with the Meadors and after tortuous negotiations, they agreed to buy back the books and objects for around $3 million.

A happy ending all around, but not for the Meadors. You see, they didn’t file an estate return with the IRS – the estate that they took through probate was below the estate tax limits. They then sold an asset of that estate for a few million dollars. A sale that was impossible to hide, especially as the whole thing ended up being the cover story in the New York Times Magazine. And a book. And a 6-part Discovery channel documentary. And law school case books.

The IRS was rather uninterested in what the Quedlinburg Treasure had been sold for and much, much more interested in what it was worth. The answer to that question was, according to every art expert in the world, priceless. The IRS interpreted priceless as over $200 million. The Meadors received an estate tax bill of $50 million, including penalties and interest.

It took over ten years of litigation for the Meadors to finally settle with the IRS.

There’s a bunch of lessons here:

- You can’t hide assets; sooner or later they’ll be found.

- Your ‘personal’ valuation of an asset is not the valuation of the IRS or other government entity.

- The ‘sale price’ is not a valuation, it’s just the sales price.

- Never assume the IRS has gone away.